BAD WEATHER (2017 ->)

“Bad Weather” is a performative sound art event centered on sound effect machines used in Baroque theatre. The idea for this performance was developed by composer and sound artist Arturas Bumšteinas, whose affair with the Baroque noise machinery began in 2012, when he was commissioned by Deutschlandradio Kultur to create a radiophonic composition for the centenary of Futurism. This affair has then resulted in an award-winning radio art project “Epiloghi. Six Ways of Saying Zangtumbtumb” (2013). Later on, he came up with an idea to reconstruct, with the help of a professional theatre carpenter, historical devices that were used to imitate the sounds of wind, rain, sea and thunder, identical to the ones whose canon settled in European theatres over the seventeenth century.

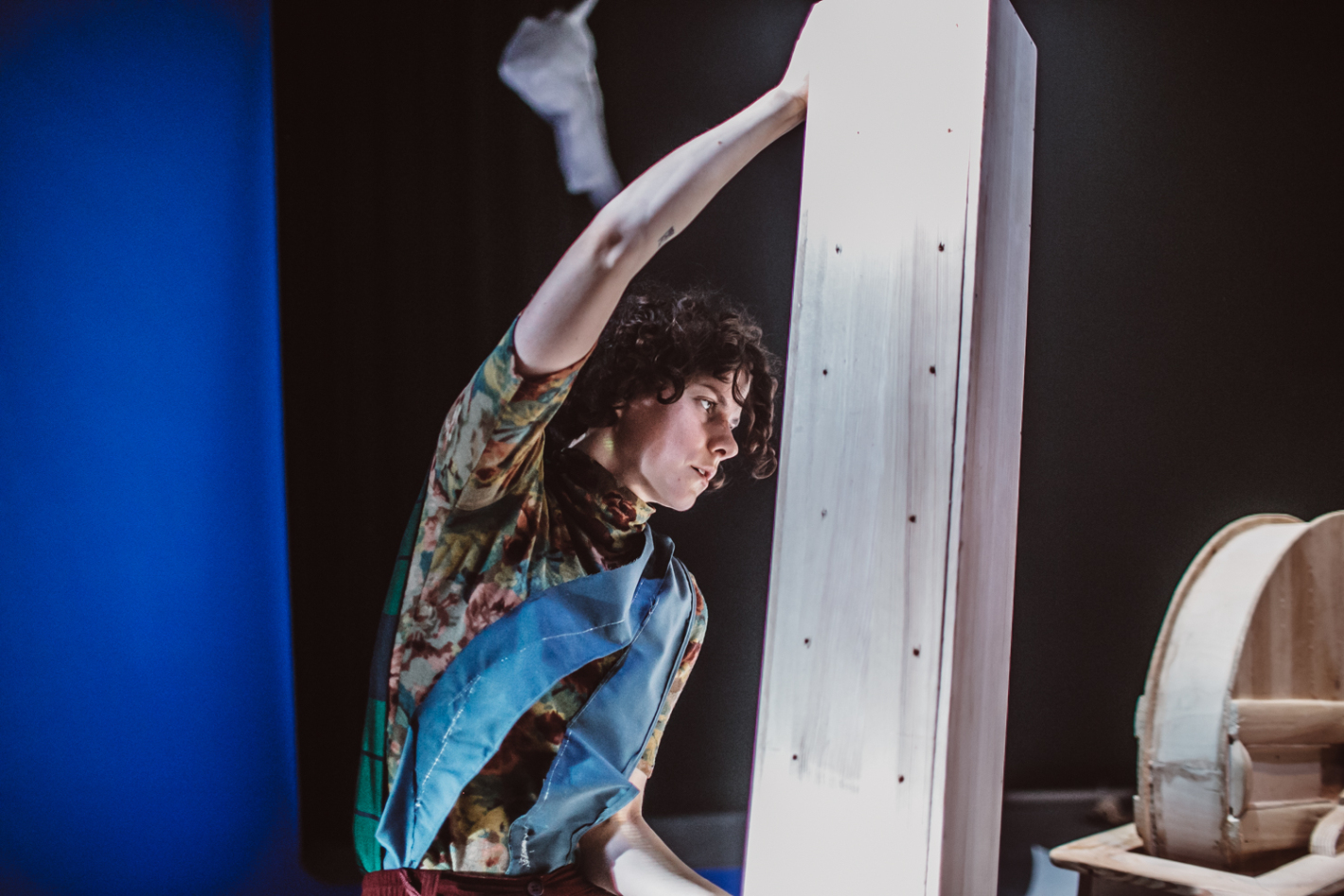

In the Baroque era, noise machines constituted but a small part of the whole theatrical illusion – the one invisible to the eye of the viewer, with its positions at the theatre’s wings and behind the scene. In “Bad Weather”, noise machines serve as generators of conceptual ‘climate.’ But like any other man-made and man-operated mechanisms, noise machines are not self-operating perpetuum mobile: their spontaneity is influenced by human (or horse) muscle tension and possible creative intention.

The ensemble of live performers is coordinated by the specially written score, in which musical notes and choreographic instructions are replaced with weather charts from various centuries and their decontextualized fragments that serve to organize the dynamics of movement and, figuratively speaking, set to rotation the ‘wheels’ of natural weather phenomena. Performance artist Ivan Cheng has written a specific performative text for “Bad Weather”, which negotiates weather as a form of representational subjectivity.

Each live version of “Bad Weather” is a little different, depending on the venue and general context of the event. And what about the singing voice...? The aria is floating around in the surround-sound space, looking for the body to pin to.

“The performers are not making sound effects per se; what they are doing is more analogous to accomplished jazz musicians improvising their way through a well-known standard.” (John Doran, The Quietus, on “Bad Weather” as premiered at Unsound Festival, October 30, 2017)

Author of the idea and stage director Arturas Bumšteinas

Librettist and text performer, original costumes: Ivan Cheng

Performers with noise machines: Gailė Griciūtė, Greta Grinevičiūtė, Aaron Kahn, Rūta Junevičiūtė (04/18), Alanas Gurinas (09/18, 12/18)

Live sound processing by Antanas Dombrovskij

Sound designer Ignas Juzokas

Lighting designer Julius Kuršis

Reconstruction of noise machinery by Ernestas Volodzka

Producer OPEROMANIJA

Duration – 50 minutes

Première – October 10–12th, 2017, “Cricoteka” Centre for the Documentation of the Art of Tadeusz Kantor, Kraków, Poland

Lithuanian Premiere - April 21, 2018, Lietuvos nacionalinio dramos teatro | Mažoji salė, Vilnius, Lithuania

- September 26, 2018, Menų Spaustuvė | Kišeninė salė, Vilnius, Lithuania

- December 16, 2018, Klaipėdos dramos teatro | Kamerinėje salėje, Klaipeda, Lithuania

- February 28, 2019, Menų Spaustuvė | Kišeninė salė, Vilnius, Lithuania

- March 2, 2019, Kauno miesto | Kameriniame teatre, Kaunas, Lithuania

Rationalising Bad Weather

Luke Howard is credited with inventing clouds. Based on his observations towards the end of the 18th century, the British chemist and amateur meteorologist offered structural typologies for clouds that accommodated temporal, geographic modifications and transformations. Following his scientific diction, these typologies quickly entered into the literary and visual arts, an abundant canon of cloud based language following.

Classification and its dissemination, which is to say, the inscribing of an ever changing climate, is precisely the tension at hand with writing and writing about the text from BAD WEATHER. The development of and repeated performances of BAD WEATHER utilise a mechanism that poses as an ecosystem. As in the case of Luke Howard and those who followed, the role of subjectivity in viewing transformations and the possibility of obsolescence should not be understood as natural. Nativity and naturalness should always be tested, devices questioned, and inherited histories at least acknowledged as such.

At the head of the performance, a rapid stream of text is incanted, a camera trained on the speaking performer in streaming broadcast on a theatrical scrim. Hovering in the genre of weather report and possessed vessel but functioning as neither, the speaker appears in continual relation to device but always elusive; a channel. A flashing image of the spoken word also appears, distorted lightning to the rumbling thunder of speech. The scrim seals an unlit stage, occupied by reconstructions of baroque noise devices, grains, and paper – designed to sound of wind, thunder, rain. This littered stage is ‘reset’ by three performers, rustlings, scrapes and functional crossings of the camera image.

But this knowledge of structure and the logic of the performance is not explained; the ‘natural state’ is never defined, though the devices are weathered, eroding from each performance. The sounds of the noise devices are selectively amplified, and sometimes processed into a sonic field for a seated audience; technology within the mechanism of theatre disorients and distorts what is made visible. Choices in the work valorise a space of not-knowing and decentralised control. Sonic devices (speaking, moving, constructed, digital) are also tasked with listening.

The mechanism is constantly displayed, if not revealed. What might it mean to be undetectable in this environment, to appear impassive? A spy listens and observes, often contracted by an external party. A spy infiltrates with discretion or camouflage, watches, before re-interpreting their gleaned knowledge. The text plays at spilling intimacies, a milieu and desire continually glimmering but not shown. Arguably, only a contoured surface is revealed. Penetrations are always by design. To align this textual strategy with the staging: is the wooden object revealing its interior in emitting sound, or is it just sonifying a performer’s gesture? The text persists with the idea of visibilities (lighthouses, theatre lights, narrativity, the stripped skin of leather, the open window) and proposed hiddens (mining tunnels, horses in vents, spies, clouds, the feathers in a pillow or down vest). In each of these instances, the potential for material or metaphorical transformation is key.

The traditional function of these noise devices was to serve as pathetic fallacy to a scene. Having played at dissolving the importance of a protagonist or soloist by placing theatre instruments on stage, the world of the foley artist is closer. Aping the baroque noise devices, every object uttered in the text is designed to mimic, illustrate, or embellish. The synthetic is the present, the processed foods of chocolate bars, corn syrup, coffee, all blurring the proposed line between instant gratification and bracing for the future.

For stretches of the writing process, references that located a designated history or site were discarded. This behaviour was proposed in response to the weighty masculine histories volleyed over – Luigo Russolo’s intonarumori, Marinetti’s aeropoems, early Krakow weather diaries, Plato, Aristophanes, on speech and rhetoric; imposed, historicised moments. Avoiding voicing through these lionised events to never justify in relation to forefathers. Wishing to locate origins elsewhere, imagined topographies to synthesise fronts and pressure systems. Delusional space had to exist. Judgements on weather are based on a negotiated idea of ideal, so how to delude this subjectivity by avoiding anchors? What could be achieved by alienating and appearing as shockingly other in a sound world based on recognition?

It merits mention that the aria sung and live processed is from Vivaldi’s only surviving oratorio, Juditha triumphans devicta Holofernis barbarie which arrives without translation, citation, and in a falsetto, moving in and out of pitch and diction. Cassetti’s latin text for this aria, Agitata infido flatu anthropocentrically projects the pleasure of home onto a sparrow tossed around by a treacherous wind, though the scansion and device of the sparrow are deployed as fallacies for the protagonist.

The final text is peppered with hooks and lines, with David Bowie is lightly mentioned with a rhythmic hook from Sound and Vision (blue blue electric blue), and his reference continues almost bitterly with the rhythmic pattern of queer desire in a verse from Heroes. Cyndi Lauper’s Time after Time is voiced by Shadow, the horse whose form or materialisation is continually negotiated in response to use value, a labor force made more obsolete and instead fetishized or infantilised. The privilege of Carly Simon’s You’re So Vain, the subject walking onto a yacht held true to the disaster fantasies of colonising ships or super yachts, the revolutionary wishes to redistribute resources, and the ungenerous position of the speaker in not speaking directly.

The string of pop hits from the eighties infiltrate a possible hierarchy of values. Phil Collins’ In the Air Tonight appears in an extended form, a bitter pleasure of lyrical anticipation, the wait for the percussion solo aligning with the expectation of operatic climax, the synthetic drums also conceptually aligned. The arrival of the Collins song was via Eminem’s Stan, in which a fan’s misinterpretation of lyrics is conveyed in rapid rhythmic verse. It is broken up by a sample of Dido singing about weather and expressing gratitude, which also explains the glimpse of Mary Mary’s Shackles (Praise You).

The logic of this détournement is consistent throughout the construction of the text. The performed text wishes to form an impression, imitate an environment, rather than be a narrative or logical argument. What designs do we deploy to understand desire? The hard line imposition on the it or curve is the cut of language and structure, a bind of rationalising on the surface of dimension.

photographs Studio FilmLOVE

trailer

longer excerpt

April 2018, National Drama Theatre, Vilnius

October 2018, Arts Printing House, Vilnius

photographs Martynas Aleksa